Making waves: Copyright in ‘Wave Fabric’ can be protected as a ‘work of artistic craftsmanship’

The Intellectual Property Enterprise Court (IPEC) has held that a fabric made with a wave design was protectable as a ‘work of artistic craftsmanship’. The judgment provides greater clarity on the scope of protection for ‘works of artistic craftsmanship’ but while it is the first UK case to consider the recent CJEU decision in Cofemel, it does not go quite as far as dealing with the issue of whether the UK’s copyright regime is aligned with EU law.

The facts:

Response, the Claimant, designs and markets clothing. The defendant, EWM is a major retailer of clothing with about 400 stores across the UK.

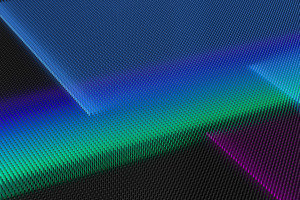

Between 2009 and 2012, Response supplied EWM with ladies’ tops made of a jacquard fabric with a design referred to as a ‘wave arrangement’. In 2012, Response sought to increase the price of the tops. This was rejected by EWM who instead sourced a similar wave fabric from alternative suppliers, having first supplied them with a sample of the original fabric.

Response issued proceedings for copyright infringement claiming that copyright subsisted in its wave arrangement design, either as a ‘graphic work’ or as a ‘work of artistic craftsmanship’.

The court ruled that the definition of a graphic work (s. 4(1)(a) Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988, “CDPA 1988”) could not be stretched to include a fabric, whether made on a loom or a knitting machine. However, HHJ Hacon found that copyright subsisted in the wave fabric on the basis that it was a ‘work of artistic craftsmanship’ under section 4(1)(c) CDPA 1988.

HHJ Hacon based his finding on the application of the definition of a ‘work of artistic craftsmanship’ in Bonz Group (Pty) Ltd v Cooke [1994] 3 NZLR 216, a decision of the New Zealand High Court. In his view, the creator of the fabric was a craftsman using his/her creative ability to produce something with aesthetic appeal. The judge was not sure if the test related to the intention of the craftsman to make something aesthetically pleasing or rather whether the work is aesthetically pleasing to at least some people. Either way, the criterion was satisfied in this case as the fabric was a commercial success, so customers must have found it aesthetically pleasing.

HHJ Hacon noted that this conclusion would not have been shared by their Lordships in George Hensher Ltd v Restawhile Upholstery (Lancs) Ltd [1976] AC 64 (the House of Lords case which considered whether a prototype for suite of furniture was a ‘work of artistic craftsmanship’) but noted that “no binding principles of law” can be taken from the Hensher judgment which bound him in the present case. Moreover, the Bonz definition had been approved twice by the UK court in the first instance judgements in Lucasfilm Ltd v Ainsworth [2008] EWHC 1878 (Ch) and Vermaat (t/a Cotton Productions) v Boncrest Ltd (No1) [2001] FSR 5.

EU law

The judge also considered the position pursuant to European law namely Article 2 of the InfoSoc Directive (2001/29/EC), which requires that Member States must provide protection to authors of a ‘work’ and the recent CJEU ruling in Cofemel-Sociedade de Vesturario SA v G-Star Raw CV (Case C-683/17).

In Cofemel, the CJEU ruled that national law could not impose a requirement of aesthetic or artistic value for copyright protection to apply, it was sufficient that the work was original (pursuant to the EU standard of originality) in that it was the author’s own intellectual creation and the expression of his/her free and creative choices.

HHJ Hacon noted his obligations to interpret UK law, i.e. the 1988 Act, so far as possible in conformity with the InfoSoc Directive (the Marleasing Principle) and therefore in conformity with the way in which that directive has been interpreted by the CJEU (i.e. as per Cofemel).

He further noted that complete conformity with Article 2 of the InfoSoc Directive, particularly as interpreted by Cofemel, would exclude any requirement for aesthetic appeal and this would be inconsistent with the definition of a ‘work of artistic craftsmanship’ as per Bonz. However, the judge noted that he did not need to go this far. Having found on the facts that the wave fabric did have aesthetic appeal the Bonz Group principle was satisfied, whether or not in law it is in fact required.

In summary, the judge concluded:

- It is possible for an author to make a work of artistic craftsmanship using a machine;

- Aesthetic appeal can be of a nature which causes a work to appeal to potential customers; and

- A work is not precluded from being a ‘work of artistic craftsmanship’ solely because multiple copies of it are subsequently made and marketed.

HHJ Hacon was satisfied that no binding English authority had been drawn to his attention which prevented him from coming to his conclusion. He subsequently found that the other jacquard fabrics used by EWM copied a substantial part of the wave design and infringement was established.

Comment:

The judge’s analysis of the Cofemel decision and the interpretation of Article 2 of the InfoSoc Directive suggests that if all that is required for copyright protection to arise is originality then the UK requirement for aesthetic appeal is redundant. However, the judge chose not to tackle this thorny issue and we instead will need to wait for another case where the artistic/aesthetic merits of an item are in issue for this to be properly considered.

Also still unanswered is the bigger question arising from recent developments of EU law as to whether the UK system of identifying and only affording protection to copyright material by reference to a specific (and closed list) category of ‘work’ (pursuant to s.1 CDPA 1988) is compatible with EU law.