How convenient is termination for convenience in Qatar?

A clause that gives a party the right to terminate a contract at their absolute discretion, is commonly referred to as ‘termination for convenience’ clause. Such right may be granted in favour of either (or both) parties, however in a normal commercial context, it is almost always a right inserted by the client, for the benefit of the client.

Inclusion of termination for convenience clauses

In uncertain times, the prevalence of termination for convenience clauses often becomes more widespread. This is usually a result of two key factors:

- There is greater hesitation by the client, fearful of what may occur over the term of the contract which may require them to abandon the project; and

- A shift in market forces, whereby consultants are more desperate for work, giving the client a significant advantage in bargaining power.

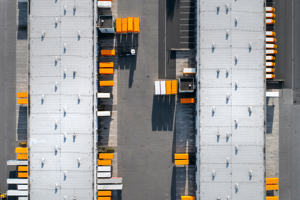

It is these two factors that perhaps explain why the inclusion of termination for convenience clauses (even during the best of times) are so common throughout the Middle East. Firstly, there are a number of elements of increased uncertainty in the region. For example, the embargo against Qatar by several Middle Eastern countries (including its three closest geographical neighbours: Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Bahrain) is a recent example of how the political structure of the region creates an uncertain commercial environment. Secondly, as most major projects are procured by the state, there is a substantial inequality in bargaining power. As a consequence, the client has the ability to issue a tender on a ‘take it or leave it’ basis, and still will receive a multitude of commercial bids.

Qatar law

In Qatar, the inclusion of termination for convenience clauses are not only common in consultancy contracts, but are a right that exists at law. Article 707 of Law No. (22) of 2004 Regarding Promulgating the Civil Code (‘Civil Code’) states as follows:

“The employer may withdraw from the contract and stop the work at any time prior to its completion, provided that the contractor shall be indemnified for all expenses incurred, all works completed, and any profit he could have made had the work been completed.”

Firstly, as can often be the case with English analysis of Arabic law, the translation itself provides some uncertainty. The above translation is as published on Al Meezan (Qatar Legal Portal), yet the word “withdraw” (as shown in the first line) is perhaps misleading. In fact, the literal translation of this word in the original Arabic text is “dissolve”. To further add to the confusion, another translation of this Article of the Civil Code uses the word “disengage”. Whilst the words “disengage” and “withdraw” are relatively interchangeable, “dissolve” is quite different. These discrepancies make it difficult to have confidence in how this Article of the Civil Code is intended to apply.

In any case, Article 707 does not provide clients with a particularly enticing option when needing to get out of a contract, because exercising this right pursuant to Article 707 will entitle the consultant to recover its expenses and lost profit. As such, it is essentially akin to the client repudiating the contract, as it carries similar payment consequences.

FIDIC Model Services Agreement

This particular provision of the Civil Code therefore requires some special consideration when drafting a termination for convenience clause in a contract to be used in Qatar. It is also the case that international standard forms may not be sufficient in this regard. By way of example, clause 4.6.1 of the FIDIC Model Services Agreement 2006 (commonly used in Qatar) provides the following termination for convenience clause:

“The Client may suspend all or part of the Services or terminate the Agreement by giving at least 56 days' notice to the Consultant, and the Consultant shall immediately make arrangements to stop the Services and minimise expenditure.”

Many lawyers reviewing such agreement on behalf of the client may initially be of the view that such clause gives the client a simple and convenient way to bring the contract to an end. However, if the contract does not address the amounts payable to the consultant upon such termination, does Article 707 come into play?

The question essentially comes down to whether or not terminating the contract for convenience pursuant to this clause 4.6.1 is deemed to be withdrawing/disengaging from the contract (or perhaps ‘dissolving’ the contract), pursuant to Article 707?

One view is that by exercising the right pursuant to clause 4.6.2, the client effectively withdraws from the contract, and as a consequence, Article 707 comes into effect. This would result in the Contractor being entitled to recover its costs and loss of profit as the FIDIC Model Services Agreement does not provide any further information about what is payable upon termination for convenience. As Article 707 does not conflict with the contract, it can be argued that it essentially provides guidance to the parties as to what is payable in that scenario.

The argument contrary to this interpretation is that terminating for convenience pursuant to an explicit term (such as clause 4.6.2) is an active measure taken by the client to bring the contract to an end, rather than withdrawing from (or dissolving) the contract pursuant to Article 707. In that case, it would only be liable for the services performed up to the date of termination. In my view, this argument is the more persuasive.

Drafting for termination for convenience

However, with conflicting views and uncertainty in the law, there are ways to avoid this risk and draft appropriate conditions for contracts used in Qatar. Most simply, the contract can be explicit about what is (and what is not) payable in the event of the contract being terminated for convenience. Article 707 is not mandatory, therefore if the contract is states that loss of profit is not payable upon termination for convenience, the potential impact of Article 707 is immediately tempered. This recommendation is not limited to Qatar, as any contract, used in civil or common law jurisdictions benefits from improved certainty and explicitly stated rights.

Effect on the tender process

As the Middle Eastern markets mature, the prevalence of termination for convenience clauses may become less common. This is because, despite the level of comfort it gives the client (particularly during uncertain times such as we are experiencing now), a termination for convenience clause will have an impact on the outcome of the tender.

There is no doubt that consultants bidding for a significant volume of services must account for the risk posed by a condition that allows the client to terminate at any moment, for any reason. This is particularly the case where recruitment of staff, purchase of specialised equipment and other mobilisation costs are substantial.

The consultants who critically take this information into account will tend to be those who can be more selective about the risks they are willing to bear in order to secure the engagement. As a consequence, the inclusion of such provisions could result in the client losing the most qualified and competent consultants through the tender process.

This is not to say that termination for convenience has no place in contracts, but there are ways to mitigate its impact on the tender.

Firstly, the client can impose specific circumstances as to when it may exercise the right to terminate for convenience. If there are particular events that the Client is fearful would have an impact on the need for the services (such as an embargo or a pandemic), it may reserve a right to terminate the contract in these specific instances only. By limiting the extent of its right to terminate, it will reduce the consultant’s risk, particularly where such matters are limited to events that:

- are not within the complete control of the Client; and

- have a relatively a low likelihood of occurring.

Secondly, the client can include in its termination for convenience clause, provisions that ‘share the pain’ if the right to terminate is exercised prior to a particular percentage of the works have been completed. This way, the client is disincentivised to terminate the contract for convenience, and the consultant is assured that part of its cost will be recovered if such right is exercised. Both the disincentive and the ability to recover part of the costs reduce the consultant’s risk which should reflect in a reduced contract price.

It is expected that as the market continues to mature throughout the Middle East, these, and other methods will be more commonly adopted, replacing a blanket right to terminate for convenience.

This article was written by Glenn Bull. For more information, please contact Glenn on +971 52 320 2596 or at glenn.bull@crsblaw.com.